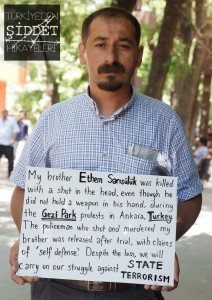

On the second day of the nationwide Gezi Park protests, June 1st, Ethem Sarısülük, a laborer and human-rights activist was shot in the head by a policeman. After spending 11 critical days at the intensive care unit, news of Ethem’s brain death arrived on June 12, only to be followed by his clinical death on June 14. Despite the hard evidence, Ahmet Sahbaz, the police officer that killed Ethem was released on the grounds of self-defense and is now pending trial. As the demonstrators keep meeting at Taksim Square every Saturday to seek justice for Ethem, the police violence that led to not only his, but also other protester’s deaths prevails. Ethem’s brother, Mustafa Sarısülük talks about the day Ethem was shot, Erdoğan’s government’s approach to Ethem’s death, and Turkey’s long-held tradition of state terrorism.

The excessive methods riot police used during the Gezi Park protests between May 31 and June 15 led the public to think that police violence is a new problem in Turkey. However, the police have already killed over 140 people since 2007. What was your point of view on the subject before the current turn of events?

“State terrorism” would actually be a better way to put it than the mere description of “police violence”. With the current turn of events, many think it as ‘the police are in favor of AKP (the ruling Justice and Development Party), hence the violence’. It’s not that – the police are an armed paramilitary force used by the state or, the current mentality. From the beginning of the Republic of Turkey, the state, with its governments and police, employed despotism, violence and massacre. Thanks to the Gezi Park protests, the oppression is now seen by the whole society.

Did you or Ethem have to face this state terror before?

After the ‘deep state’ events in the 90’s, I felt an urge to be involved because of the level of human rights violations, violence towards the people and extrajudicial killings. Even as a kid at junior high, Ethem used to join me at the protests. Since then, we exercised our rights and freedoms of gathering, protest and expression. We both faced violence and custodies repeatedly.

Before AKP came to power in 2002, the executor of violence was mainly the military. Now, with the AKP government in power for 10 years, the violence intensified within the police force alone. How do you interpret the changes over the last decade?

Even though AKP has been claiming that they are “defending human rights and dissolving the deep state”, they have never met the necessities of that task. There happens to be no change concerning the police-related extrajudicial killings or tortures. For me, the killing of Ugur Kaymaz summarizes the decade best: When the alleged terrorist was found dead with his father, there were more bullets in his body than his age – he was 12. The fact that the murderers of Ugur still remain unknown shows that AKP continues the state tradition. Today, people who shout “solidarity against fascism” along the streets point their anger not only to the AKP policies, but also to the state tradition that lies beneath them.

Many unexpressed displeasures of the last decade came to the surface after the unfathomable insistence to build a shopping mall in Taksim’s Gezi Park. The police crackdown at Gezi Park against the peaceful protesters on May 31st triggered the protests in other cities. What was it like in Ankara on June 1st?

I heard about the police attack in Taksim’s Gezi Park on May 31st, but because of work, I had to wait until Saturday June 1st to join the protests. Ethem, however, was out there as early as the 31st, wearing his boiler suit. Come Saturday, I was also at Kızılay Square when the police started to attack people with extreme force. Some kids and children who got their skulls injured and eyes blinded were there protesting for the first time in their lives. In that turmoil, I started to protect the people around me. The police were so harsh and virulent that their acts at the time cannot be just called ‘disproportionate use of force’. They were aiming at civilians’ heads and upper body parts while shooting tear gas and rubber bullets. People who were unfamiliar with the police were outrageous after that kind of unexpected attack. I kept helping people with broken arms and legs, as the police terror continued in the morning. Then I heard several gunshots around 1 pm.

Throughout the protests, the government tried to justify the police brutality by saying that the police officers had been working under poor conditions for very long hours. However, on June 1st, the events in Ankara had just started, and the police weren’t tired or sleepless.

I really wish I had a camera on me that day so that I could document what I saw. The police were trying to kill people – even I alone carried tens of heavily wounded. I saw several policemen lying on the ground, positioning themselves just like marksmen. After taking their time to aim, they would shoot gas canisters directly at people’s heads. I witnessed the police taking random shots into the air with their guns. As soon as I had arrived at Kızılay Square on Saturday, I knew that police brutality would lead to grieve consequences and deaths on that day. If the youth hadn’t acted with their reason against police brutality, there could have even been a massacre at the square.

When did you find out that Ethem was shot?

About an hour before the police shot him, Ethem had already got wounded while trying to protect a woman wearing a headscarf – when the police targeted people to shoot tear gas, he had used himself as a shield. One canister had hit him at the back of his head. We learned about this backstory from Ethem’s friends when the doctors found out that his skull was broken. Ethem would always be on the forefront in such events, so he was on my mind throughout the time we were at the square. Just when I started searching for him, we heard a few gunshots. Since I had seen the police shooting at the air at a number of different places on the same day, it didn’t occur to me that someone could have been shot at the instant. Then I saw a stretcher taken to an ambulance in the distance, but again, it had never occurred to me that it could have been Ethem. It was only when we received a call from the hospital that we understood the situation.

What happened after you went to the hospital?

I knew my brother wouldn’t live as soon as I saw him. I went to the doctors and asked them for the results of the brain tomography. They were surprised to see me with such demand instead of asking how the patient was. When we examined the films with the doctors, we saw the bullet still in Ethem’s brain. It was lodged deep in his brain, and had ripped a hole in both hemispheres.

One of the government-sourced claims at the time was that Ethem had been wounded by the stones thrown by the protesters. How did the truth get out?

The video footage showing the incident is nothing but hard evidence. The police officer, Ahmet Şahbaz, intervenes the crowd alone, kicks a protestor, calmly draws his gun and shoots several rounds. One of the bullets hits Ethem on the head. The murder is crystal clear, yet, at the time there was a nationwide censorship going on. We counteracted the censorship by spreading the images showing the moment of the incident on social media and getting into contact with non-governmental organizations. Ethem’s brain death occurred a week after being shot, but we waited for a few days more, hoping that there may be an improvement. On June 12, when we stated to the public that Ethem’s brain death had occured, the Ministry of Health denied us and stated that Ethem was in a coma and that his situation was improving. We lost Ethem on June 14.

On 16 June, the police cracked down on the funeral and its company and the peaceful crowd that had gathered for the commemoration where Ethem had died. What happened that day?

A while after Ethem’s brain death happened I visited the managerial chief of the hospital. It was a week before the funeral. When I entered the room I came across two people in suits who I guessed were police. I started to speak with the person who I learnt was the General Manager Assistant of Security. I told him, “We have lost Ethem now. We wish he’d survive and return to us, but we aren’t fooling ourselves. Our desire is that you respect our funeral and our ceremony. If you do not, it is your choice, and you will suffer the consequences.” He gave us a guarantee that we could have the funeral and that nothing adverse would happen during the funeral. Despite this conversation, they attacked our funeral. The truth is, as Ethem’s family we did not demand a mass funeral ceremony but because the public, NGOs, political parties, and leftist bodies took so much ownership of Ethem as well, it was decided that after a commemoration on 16 June where Ethem had been shot at Kızılay Square, the funeral would be sent to our hometown. When I went to Kızılay that day, I saw the police barricading the area. I learnt from my family that the djemevi where the funeral was taken was blocked and that the police and the military had surrounded the hearse. We made a telephone call to the governor’s office and learnt that there would be no intervention by the police. But before long, the police cracked down on the crowd who was peacefully waiting and leaving flowers on the spot where Ethem was shot. We couldn’t make any sense of the attack on those who were there to mourn. We saw that the government couldn’t even tolerate a commemoration. Since the government had attacked funerals and hijacked them from their families to bury them at homeless’ graveyards in the past, I was not surprised to see what we went through.

On June 24, Prime Minister Erdoğan made the statement, “the police have stayed within the limits of the law, and written an epic tale of heroism.” On the very same day, the police officer that killed Ethem faced a judge and was released, pending trial, on the grounds of self-defense. Did this verdict lower your expectations for the judicial process to follow?

The Prime Minister had declared at the outset that he would not “let anyone bully [his] police”. We therefore had predicted that the judicial process would unfold the way it did.

The investigation at the site of the incident, expert reports, eyewitness statements, and video footage all point to murder. The judge considered neither these, nor my brother’s autopsy report nor the ballistic report as hard evidence.

Testimony records indicate that the police officer who killed Ethem was calm and conscious at the time of the murder. Do you think there were any circumstances that would justify a self-defense claim at the time of the incident?

Not at all. While other police officers are retreating upon their chief’s command, the one that killed Ethem charges with great hatred, kicks one of the protesters, and gets in the middle of the crowd. He then calmly draws his weapon and fires it.

Another argument for the court to release the officer suspected of murder was that there was low risk of him destroying evidence or fleeing the country, as he is a public servant. Are you concerned about a possible spoliation of evidence?

The court made a very peculiar decision: Is it not easier for a public servant, that is, a police officer, to talk to witnesses and modify other pieces of evidence? Videos, ballistic and autopsy reports, and expert statements reveal everything. Because they were too late to destroy evidence, all they could do was to detain and arrest our witnesses. Instead of destroying evidence, they are busy with a smear campaign. They are showing images on TV that allege Ethem had burnt a Turkish flag. I raised that boy; I know he would never do such a thing. They are also trying to mislead public opinion by showing pictures of him in camouflage gear, holding a gun. Ethem was a welder, and about two months ago he worked at the construction of military guard cabins in Hakkari and Şırnak. They presented those pictures as evidence that Ethem was a member of various terrorist groups. In truth, he also had pictures taken of him with the other workers and soldiers deployed at the site. They carry out such smear campaigns in order to prevent people from embracing Ethem. At any rate, would burning a flag or being a member of an armed terrorist group warrant being murdered in the middle of the street by the police? When people break the law, they are tried by impartial courts, and sentenced if necessary. But these campaigns aim to legitimize Ethem’s murder. They will not be able to resolve this issue unless they arrest the millions that have embraced Ethem.

The poster that was put up by Ankara’s mayor Gökçek, the same person that accused foreign media outlets for running a conspiracy against Turkey.

Ankara’s mayor, Melih Gökçek had a poster put up at the site where Ethem was shot by the police that read, “Esteemed Turkish police, Ankara is proud of you”. He also claimed on TV programs that Ethem’s injuries were due to stones thrown during the protest. Did mayor’s attitude surprise you?

I will not respond to someone like him. The fact that he makes daily TV appearances glorifying the countrywide police brutality that started in Taksim stems from the aggressive, fascistic approach he has adopted against the people. The poster he had put up, and his claim that Ethem was wounded from stones thrown at the rally definitely saddened our family. He could have learnt the truth from us; I would have spoken and shared with him the factual information we keep – just like I have with everyone else. But Gökçek has vowed to defend his state, his AKP against the people. It would have been wrong to expect a different attitude from him.

It is common in Turkey to justify extrajudicial killings at the hands of the police with excuses like sleep deprivation, gruelling work conditions, ‘ricocheted bullets’, or testimonies such as ‘my foot slipped’; and murders go unpunished. Are these injustices finally being understood by larger groups of people?

What separates the police’s slaying of Ethem from other incidents of extrajudicial punishment is that it happened in front of the whole public and there is video evidence of it. The murders of Uğur Kaymaz[i], Baran Tursun, Cem Aygün and many others were justified with statements like “these people are all terrorists/members of radical groups/drug addicts”. Ethem was killed in front of the people who took to the streets to protest police brutality. For years, families of people who were subjected to police terrorism could not receive enough public support, because the state used its own communication tools to marginalize the victims. People are now more aware of the state’s rhetoric, and their blindfolds have been lifted at least a little bit. They now see the police for what it is, and how the state has been covering up its crimes. We have always paid a price, but this time it has been too much. Living under this government, I knew that something like this might happen to Ethem or me at one point. Is it a coincidence that those who are subjected to state terrorism are the ones that defend human rights, labour, peace, freedom, and compassion?

Turkish to English translation: Deniz Tan Celasun, Emre Esensoy, Oliver Barış Bridge

Interview: Dogu Eroglu

14 July 2013

Source: siddethikayeleri.com

This post is also available in: Turkish